Diamond in the Rough by Todd Mason November, 2020

As fate would have it, my first composition teacher at Juilliard was the American composer David Diamond. I had heard a few stories of him being “difficult” but I wasn’t terribly worried because I was so thrilled to be attending the most famous music school in America, The Juilliard School.

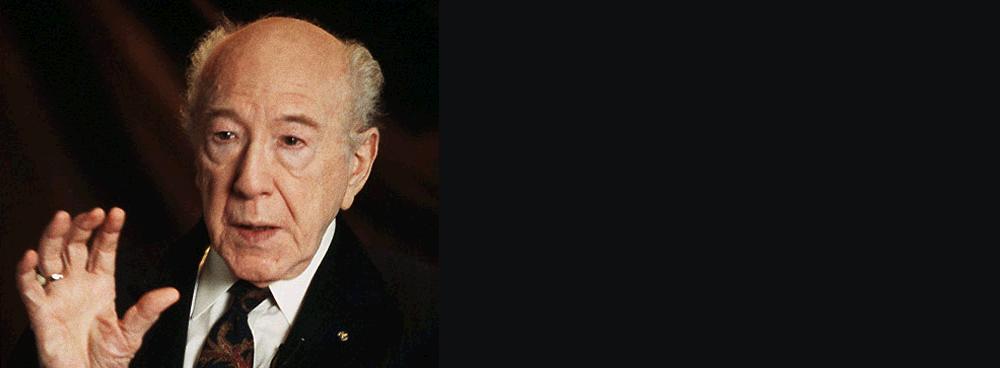

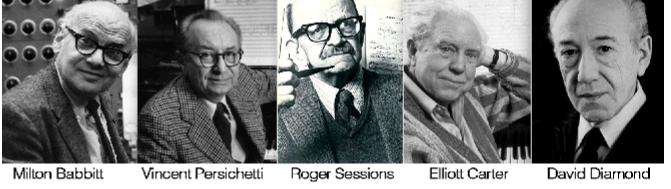

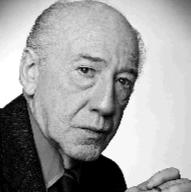

During my seven years at Juilliard, I would meet, and see up close, some of the rock stars of the classical music world including Herbert Von Karajan, Aaron Copland, Arthur Rubinstein, and of course Leonard Bernstein. And, being from Los Angeles, New York City itself was a caffeinating experience of impossibly high skyscrapers and 24/7 traffic, police sirens, restaurants from every country on the planet, businesses of almost any kind you could imagine, and torrents of people everywhere. The whole place was a fantastic, immersive experience. So, at first, I wasn’t terribly bothered by my first teacher being a bit eccentric. At the fall Juilliard entrance jury examination, which was extremely nerve-racking - some would say terrifying - there were only a few openings for new composition students, and seated in front of me were Milton Babbitt, Vincent Persichetti, Roger Sessions, Elliot Carter and David Diamond. One by one, they would ask a few probing questions and I tried my best to sound sophisticated beyond my years and then it was David Diamond’s turn. As it turned out, I had been intensely studying the late Beethoven quartets to the point that I could recognize almost any series of notes and tell you exactly which quartet they were from and which instrument was playing them. David Diamond asked me which composer I admired the most. Sensing that this might be a trick question - perhaps some of the teachers were hoping I might say their name to ingratiate myself - I just told the truth and I said “Beethoven.” With his small body, perfume and sour lemon expression, Diamond walked over to the piano and said, in a surprisingly low and overly dramatic voice, “Well, if you say you admire Beethoven so much, I suppose you can tell me what this is from.” Then he thought for a minute and played (not very well) about seven notes. But I knew what it was. I told him it was from Op. 135, 2nd movement, and that was the viola line. As if in a court room, he looked over at the others with an expression suggesting, “well, I have no more questions.” I recall Milton Babbitt, the brilliant and witty undoer of Diamond, looking amused. The good news was that I passed the exam and was admitted into the composition department at Juilliard, which was certainly a high point in my young life. The bad news is that the teacher that selected me to be his student was David Diamond. As my studies ensued in that very little room, #504, near the top of the elevators on the fifth floor, I soon discovered what a peculiar man he was. On the door, he had taped a handwritten note which said “knock, then wait 5-minutes.” We could never figure out what that was for. He had Coke-bottle thick glasses and what appeared to be too much pancake makeup covering a rough complexion. He always wore a tailored suit with a perfectly folded handkerchief and, for the most part, conducted himself professionally even if he used pretentious words and sentences that were often confusing if not meaningless. I always thought David Diamond was going to give me wonderful insights into composers like Beethoven and Bartók but often times what I got instead were his unique theories about note relationships and “architecture in music.” I remember in one lesson he got a bit off topic and spoke about an idea he had that it was the wind that held up some of the highest skyscrapers. I continued to study with him, but by the second year, things began to get more strained. I had discovered that he wasn’t as interested in sharing a deep understanding of great composers as much as expressing his own personal stories about the shortcomings of various people. In the TMI category, he claimed that he had been “very close” with Leonard Bernstein but that Bernstein had let him down. “He walked out on me.” Diamond implied that it was Bernstein who was the impossible man!

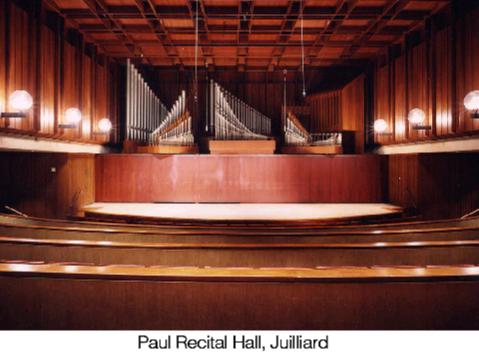

At the school cafeteria, on the second floor, it became common for some of the other Diamond students to share a table and stories, and trying to imitate Diamond’s theatrical voice, I told the high F# story to the amusement of several others. Diamond, given half a chance, would often complain to his students that his own music wasn’t performed nearly enough, lamenting “Why won’t they play me? They’ve been poisoned against me! And I know it’s because of that awful person ..” (fill in the blank) This always seemed petty and counterproductive. I’ve always thought that there were several of his pieces that do have beautiful moments including his 1st and 2nd symphonies which are a bit Copland-esque but with Diamond's own engaging ideas, energy and colors, and they show a high level of expertise, writing for the orchestra. His 2nd Violin Concerto is also to be recommended. In spite of his protestations, some of his music has actually been performed quite a bit. Diamond originally trained as a violinist and I was able to learn from him a few things about how better to write for the violin. Oddly enough, I’ve always thought that his own string quartets were not his best works. They’re complicated and frustrating to listen to because one feels that there’s no good development going on, but more of an endless jumble of disconnected angular ideas. It’s as if the music is guided by a terrible insecurity that there might be something, anything, that sounds like somebody else. He would often say to students “Oh, well, you’ve got Schubert in that line” as if that was a terrible error that had to be excised. Recently, I asked Arnold Steinhardt, the 1st violinist of the famed Guarneri String Quartet, if they’d ever played or read through any of the Diamond quartets and he said, quite diplomatically, “Oh yes, David Diamond. No, we never got around to those.” The other thing I discovered was that Diamond wouldn’t often remember what we had discussed just the previous week. So, one time, perhaps feeling a bit annoyed, I didn’t change anything in one piece and I brought it in and showed it to him anyway and he said “Ah, you see how much better this works now? You should listen to me more!” (said with a bit of tongue-in-cheek grin but mostly dead serious - a warning?) So, when I was nearing the completion of my own string quartet, I decided I would only show him bits and pieces of it but not the latest part that I was working on because I didn’t want to waste time or have him mess with it. When I finally finished it, just a few days before the performance at Juilliard’s recital auditorium, Paul Hall, I very briefly showed it to him and he madly went through it, in the hallway, staring at it from only a few inches away, grimacing, and he flipped to the last page and saw that I had indicated a slowing of the tempo at the end to broaden the material as it reached its final crescendo moments. He said, angrily, “you must have an accelerando at the end. It has to be an accelerando!” The day before the premiere, I ran into him again as I was walking in front of the school and without any pleasantries he said “did you make it an accelerando?” Knowing that he would be at the performance, I told him that I didn’t want to do any last minute surgery because the quartet group had just finished their rehearsals and I decided to keep it with a slowing at the end because it worked quite well. That was enough to set him on fire. “Last minute surgery? Is that what you think of my teaching? I was getting commissions before you were born...” In spite of the cold wind outside, he went on and on about how I didn’t know anything and that I would see what a mistake I was making. At the performance - I had invited many of my friends, composition colleagues and a few parents as well - of course David Diamond also showed up. In spite of his dire prediction, the performance went extremely well with a long applause and, afterward, in the green room, many came in and were smiling, very upbeat and happy and I felt as though the whole thing had gone wonderfully well and I had escaped the whole problem Diamond had warned about — because you couldn’t I suspect it was all about loyalty. I don’t think David Diamond really cared if the music ended fast or slow, with F# or G natural, but he cared very much if he thought you were loyal to him and respected his ideas. If he suspected you were no longer loyal, you were an instant enemy of the state. The next day, he wrote a five-page letter to a good friend of mine saying that I had “poisoned his weekend” with my “impudence which he could not write off as mere California adolescence.” (He didn’t much care for California) He added that my quartet “could’ve ended like a Roman candle but instead was a limp prick.” (gee, thanks)

Over the years, David Diamond ended up saying some very nice things about me to others and even recommended some scholarships and career advice. Years later, I heard that he had told a mutual friend that I was “extremely talented.” David Diamond didn’t like many people but I do think he genuinely loved music which became the secret sanctuary of his difficult life. He had an almost encyclopedic knowledge of 20th-century music. When he died, in 2005, the New York Times featured a front page article calling him an “Intensely lyrical, major 20th century composer.”

I look back with a very mixed set of memories for David Diamond. I have great respect for his relentless pursuit of his own brand of tonalism and optimism in his music. It’s even possible that he may finally get the last laugh from some of the experimentalists of the 20th century, many of whom have been largely forgotten. But I’ll never forget the other David Diamond who more often resembled Captain Queeg from The Caine Mutiny, angrily questioning about the strawberries, than the elder statesmen of 20th century American music. He was a complex man and someone you didn’t want to tangle with but could almost never avoid doing so. ______________

Mason's compositions have been played by the Juilliard Orchestra, The Sofia Philharmonic, the Budapest Scoring Orchestra, the Azusa Pacific Symphony, The Lyris Quartet, The Angeles Quartet, The Argus Quartet, The Debussy Trio, The Los Angeles Wind Quintet, the SAKURA cello quintet, The Alex Iles Brass Quintet, The Saguaro Piano Trio, The Vieness Piano Duo, and many leading members of the LA Opera Orchestra, Los Angeles Philharmonic. Mason’s music has been performed at the Lancaster Summer Arts Festival, the Astoria Music Festival (where he was Composer in Residence for 2 years), the Laguna Beach Arts Festival, Carlsbad Music Festival, Piano Spheres, Mount Wilson Concerts in the Dome, Chamber Music Palisades, Sunset ChamberFest (Mason was Composer in Residence 2019), at USC, UCLA, and by many other prominent chamber groups. Mason offers a popular chamber music series in his West L.A. home, showcasing leading ensembles and premiering new works.. |

|

In 1974, the building itself was impressive and still new, sitting at the north end of the new Lincoln Center and, in spite of the fact that one critic called the new Juilliard building “Neo-Aztec nothing,” I loved it. It represented the ultimate in American high culture and looked modern and important.

In 1974, the building itself was impressive and still new, sitting at the north end of the new Lincoln Center and, in spite of the fact that one critic called the new Juilliard building “Neo-Aztec nothing,” I loved it. It represented the ultimate in American high culture and looked modern and important. I hadn’t slept for 2 nights because I knew enough to know that these were the high priests of mid 20th

I hadn’t slept for 2 nights because I knew enough to know that these were the high priests of mid 20th Diamond loved to talk about his time in Italy, smiling, as if that conveyed a wonderful sort of cosmopolitan air to his observations about almost everything including of course, new music. He had strong musical biases about how one note should always go to another and one key should never follow another.

Diamond loved to talk about his time in Italy, smiling, as if that conveyed a wonderful sort of cosmopolitan air to his observations about almost everything including of course, new music. He had strong musical biases about how one note should always go to another and one key should never follow another.

really argue with this very warm and positive reaction! But then, like a dark cloud, Diamond burst into the room and started pointing his finger at me. There was no tongue-in-cheek this time. He was outraged and wanted everyone to know it. He said, very l

really argue with this very warm and positive reaction! But then, like a dark cloud, Diamond burst into the room and started pointing his finger at me. There was no tongue-in-cheek this time. He was outraged and wanted everyone to know it. He said, very l Needless to say, I quietly began to look for other teachers at Juilliard. After discussing the matter with the president of Juilliard, Peter Mennin, a fine composer himself who knew well the personality of David Diamond, Mennin suggested my next teacher should be Roger Sessions who had gained fame producing the 1930s Copland-Session concerts. Sessions was quite elderly when I took lessons from him and even a bit stern but was refreshingly normal and relatively easy to get along with. I learned some valuable things about orchestration from him. Then I had the privilege to study, for two years, with Elliot Carter who was probably the exact opposite of David Diamond — very secure, widely respected, friendly, non-confrontational, and genuinely helpful. Carter was the best teacher of all of them.

Needless to say, I quietly began to look for other teachers at Juilliard. After discussing the matter with the president of Juilliard, Peter Mennin, a fine composer himself who knew well the personality of David Diamond, Mennin suggested my next teacher should be Roger Sessions who had gained fame producing the 1930s Copland-Session concerts. Sessions was quite elderly when I took lessons from him and even a bit stern but was refreshingly normal and relatively easy to get along with. I learned some valuable things about orchestration from him. Then I had the privilege to study, for two years, with Elliot Carter who was probably the exact opposite of David Diamond — very secure, widely respected, friendly, non-confrontational, and genuinely helpful. Carter was the best teacher of all of them. One has to sift through Diamond’s music but there are some gems. I would encourage people to listen to a few of his symphonies like the 1st and 2nd and his Rounds for Strings (1944)

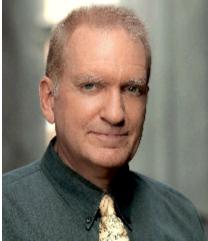

One has to sift through Diamond’s music but there are some gems. I would encourage people to listen to a few of his symphonies like the 1st and 2nd and his Rounds for Strings (1944)  Todd Mason, a Los Angeles native, received his master's in Composition from The Juilliard School, studying with David Diamond, Peter Mennin, Roger Sessions, and Elliott Carter. Mason received the Rodgers & Hammerstein Juilliard Scholarship, Juilliard's Marion Freschl Award for a composition for voice and orchestra, first place in the National Federation of Music Clubs composition contest, First Place in the Lancaster Summer Arts Festival, and the ASCAP Young Composers award, presented by Aaron Copland.

Todd Mason, a Los Angeles native, received his master's in Composition from The Juilliard School, studying with David Diamond, Peter Mennin, Roger Sessions, and Elliott Carter. Mason received the Rodgers & Hammerstein Juilliard Scholarship, Juilliard's Marion Freschl Award for a composition for voice and orchestra, first place in the National Federation of Music Clubs composition contest, First Place in the Lancaster Summer Arts Festival, and the ASCAP Young Composers award, presented by Aaron Copland.